Michael Bay, the TV commercial director who went on to make

Bad Boys,

The Rock and

Armageddon, has history on his side. Today’s maker of colossally stupid, crowd-pleasing (or in Bay’s case, crowd-bullying) entertainment is tomorrow’s critical darling. Maestros of crude sensationalism, schlock and melodrama, once derided, now celebrated, include Frank Tashlin, Sam Fuller, Russ Meyer, Jack Hill and Douglas Sirk. Joel Schumacher? Any day now.

Decades removed from their fashionable contexts, these directors’ films can now be appreciated for their stylistic abandon and rather alien tableaux (a good pop oldie, seen through a new generation's eyes, is often as exotic and colorful as an Indian musical or Hong Kong genre-mash.) We can now appreciate the blinding three-point lighting and taffy colors of a Tashlin CinemaScope romp for their sheer textural richness. Such films were the Jim Carrey toss-offs of their time (especially the Jerry Lewis films). How will the work of Attention Deficit cases like McG (

Charlie’s Angels), Brett Ratner (

Rush Hour), Rob Cohen (

XXX) and Bay strike us when the product placements and album tie-ins are no longer the films’ primary business? These horrible, feverishly exciting movies might just reach us in the strangest places.

Make no mistake: Bay demonstrates his stupidity regularly and proudly. And not just in his directing choices. Consider this exchange between Bay and internet fanboy Nelson Argueta:

Argueta: I had a very ultra-orthodox film studies teacher...

Bay: Like how?

Argueta: Well, to begin with, she was very snobbish. And she ragged on how cinematic codes and rules are being broken, and the usual blah-blah-blah given to film students. She also praised Citizen Kane day and night and said the usual stuff about it being the greatest movie of all time, etc. And how the movies have lost their true purpose, become too commercial. You know, all the stuff taught to film students here in New England.

Bay: What you need to tell her from a very big director is that there are no rules in film. And any film teacher that teaches rules is wrong. Citizen Kane, when it came out, it was a very mocked film. People did not like it. It was very unrespected. It was thought of at the time as very uncool. But he wasn't the inventor of all that stuff. All that stuff had been done in other movies, through silent movies, through musicals, yadda-yadda-yadda. But it was the first movie to really put all those things together into a movie. If she would've taught Orsen Wells, he would've laughed at her.

Argueta: When some of us in film class mentioned that we liked Armageddon, she labeled us an "easily impressed minds."

Bay: What you need to tell her is that Armageddon is the 8th highest grossing movie of all time worldwide.

Argueta: It's 4th in Japan right?

Bay: It's 3rd I heard. I think its E.T., Jurassic Park and then Armageddon. Doesn't she like exciting movies?

Argueta: Nope. She goes on to say that movies should move us to see the depth in humanity and...

Bay: Well, she's wrong.

Yet Bay’s childish lack of comprehension is his talent as much as his albatross. His fidgety desire to hack away everything “uncool” from his movies gives them an undeniable kineticism. Chaotic closeups shot with long lenses through veils of steam, rain, sparks and debris are welded together in brief, jangled fragments. Nothing that every hack from Tony Scott (the original Michael Bay) to Richard Donner hasn’t employed. But Bay’s fragments are the briefest and most jangled of all, and he usually sets them in motion from the opening credits. He has taken the Bruckheimer/car commercial esthetic to its logical extreme. This style delivers exposition, crisis and resolution all with the same spastic eye. Bay’s films don’t build; they start at a pitch of rabid hysteria and hold that note for two hours, even if his “voice” begins to flutter and crack. What makes them stupid is their detachment from every consideration but the need for speed. Even when addressing an abysmal horror like the massacre at Pearl Harbor, Bay smashes objects together like a boy playing in the tub with toy warships. In a Today show appearance during Pearl Harbor's initial release, he gleefully pointed out the opportunities he seized to "blow stuff up" from the deck of an aircraft carrier.

Pearl Harbor and

Armageddon pretend to celebrate American jingoist perseverance in the face of monstrous odds, but they’re really about the visual majesty of mass destruction.

Just after 9/11, several cultural scholars wrote of the undeniable beauty and power of the event--those gently pancaking towers and the bent exoskeletons they left behind in a crater of ash. In a culture of Old Testament literalism, the outrage over such comments was instant and unforgiving. But Bay’s movies make the same kind of statement visually, to applause. A Bay 9/11 film would have reproduced the tower collapses faithfully, but in an avalanche of montage that makes the moment more of an awesome display to be answered in kind than an awful obscenity to provoke lifetimes of contemplation. The moment when a smirking George W. Bush stood amongst the rubble and corpses to vow revenge would be signature Bay: An atrocity ameliorated by the opportunity for adventure it affords.

We live in the era of the Michael Bay presidency, in which expensive, bloody adventure is its own reward. Our president’s insipid, pandering comments on serious, world-threatening matters mirror Bay’s superficially serious filmmaking. Since the administration has already tapped him for advice on possible doomsday scenarios, it’s a wonder that President Bush hasn’t yet knighted him as Chief Propagandist. (Revisiting Bay’s

Pearl Harbor, one could easily suspect he already has.)

In the sense of auteur ownership, The Island is not Bay’s

E.T. (though its stratospheric pretensions allow lobotomized broadcast critics to call it his masterpiece.) The film is Bay’s

Jurassic Park, an opportunity to deploy all his stylistic hallmarks in one Olympic-sized arena. It’s hard to imagine that Bay saw much more than that in the movie’s screenplay. Damn shame: Written by Caspian Tredwell-Owen with the help of some script doctors,

The Island screenplay ranks with the great John Frankenheimer thrillers of American delusion,

Seconds and

The Manchurian Candidate.

The script is overstuffed with more ideas about the constellation of corporate fiefdoms Benjamin Barber calls McWorld than

1984 and

Brazil squared. It’s all molded into an engaging and explosively satisfying structure. Imagine George Lucas making

THX-1138 in the propulsive, personable style of the original

Star Wars. The story explores age-old philosophical woes fielded by Plato and Shakespeare on up to Ursula K. Leguin and the Wachowski Brothers. In the film’s allegorical underground society, clones unwittingly raised as live organ donors for rich people live in comfortable ignorance of their doom. They wait to be chosen in a lottery that promises the winner a permanent vacation on “the island”—described as a “pathogen free” tropical paradise.

Basically, the Island is the same dream we all work for, 401k documents in hand. The clones seem to represent Americans, Westerners in general, Third World laborers and anyone else who toils for a lifetime without ever fully understanding the product of his labor or the degree to which his efforts are self-destructive.

Bay seems to have a superficial grasp of these concepts, but an allegory of corporate hegemony and deception is clearly not his main obsession here. As a darling of the major studios and ad agencies, he’s unlikely to have much against Big Business.

Instead, Bay turns

The Island into an urban battle between Joe Six-Pack and the Metrosexuals. In all of Bay’s high-grossing films, straight-talking, sawdust covered Real Men must contend with mincing, duplicitous paper-pushers to Get the Job Done. Just as Terry Gilliam’s quixotic individualists partially dramatize the director’s travails in Hollywod’s conference rooms, Bay’s heroes seem to mirror his love-hate relationship with urban sophistication. Bay loves sleek, gargantuan big city architecture but hates the snotty gatekeepers. His camera caresses glass and metal surfaces with more rapturous attention than it does Johanssen’s curves. And his awe of trains, planes and automobiles takes you back to the third grade. (When clone Lincoln Six-Echo (Ewan McGregor) sees his first motorcycle, he says he has no idea what it is, “but I want one.” For Bay, coveting cool rides and gear isn’t just a trait of adolescents in a decadent consumerist society; it’s a primal urge.)

Like a kid in a posh department store, Bay appreciates the pretty lights and immaculate tile, but he can’t wait to topple the coat racks. It’s a video game esthetic (and impulse): Glimmering techno-opulence as a stage for destruction.

Die Hard, with its elegant Los Angeles skycraper-turned-slaughterhouse, is the template. The antiseptic underground cloning compound in The Island could also be Bay’s impression of Los Angeles: Flatscreens deliver sunny greetings inside crystal elevators; moussed and manicured clones in white jumpsuits drink Aquafina in what looks like a trendy Melrose lounge. Lincoln-Six complains about having to eat Tofu and veggie shakes, begging in vain for some bacon and eggs. (He has no idea that his health regimen is designed to keep his liver in pristine condition for the client who needs it.)

The compound’s main thoroughfare has the bland corporate park look of

THX-1338—a comparison doubly hard to shake because of the clones’ white jumpsuits and the creepily solicitous electronic greetings dominating every space—urinals, even. It is here that the trim, tailored Metrosexuals (my term for them, not the filmmakers’) police the clones’ behavior with the help of bouncer-like security goons. All that’s missing is a velvet rope. Like Lincoln-Six, many of the male clones grumble about having to be polite, groomed and rigorously health-conscious at all times. This is Bay, a Maxim, sports bar kinda guy, taking light jabs at Queer-Eyed, front office culture, where an average Joe can’t even get a damn piece of bacon without catching grief.

Down in the dingy boiler rooms of this place, Lincoln, who has been consciously alive for only three years (despite

Blade Runner style pre-programmed “memories”), gets a taste of real life from gruff mechanic McCord (Steve Buscemi). McCord schools him in urban cynicism (“What’s God?” Lincoln asks with a child’s sincerity; “You know when you want something really bad and you close your eyes and wish for it?” begins McCord's explanation. “Well, God’s the guy who ignores you”). The outer borough accents and shit-talking of Buscemi and his fellow working-stiffs suggest service-level Manhattan, especially when grubby McCord tries to chit-chat with a higher-up, who completely ignores him. That’s the way it would go down in the feudal Gotham of Giuliani-Trump-Bloomberg. It also characterizes Los Angeles, the most effortlessly segregated metropolis in America.

Bay seems to believe that the infantile jokes and putdowns that his ethnic working-stiffs utter help cut through any pretension that his presumably restless audience might sniff. And so, every two reels or so, he must inject a variation on that moment in Superman when a gaudily pimped-out Soul Brother bumped into the superhero and cooed, “Saaay Jim, that’s a baaad out-fit!”

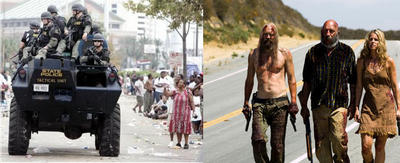

While all of this colorful nonsense buries the screenplay’s potential for greatness, the film has, as hinted above, something that reaches us in a strange place: The action scenes. When Lincoln and Jordan escape the cloning compound and flee to L.A. with million-dollar mercenaries on their tail, Bay creates stunning montage. Cinematographer Mauro Fiore and whoever served as his lab colorist make the mercs look like predatory crows in their jet-black SWAT gear. Djimon Honsou, as the main merc, coordinates the attack in a suit almost as sable as his skin. In Bay’s low-angle camera swoops, Honsou is a human panther. Fiore (or the second unit camera team) sprinkles on the burnished Bruckheimer look familiar from

Top Gun through

Pearl Harbor—the golden sunset patina described as a “Miller Time” glow by dumb movie execs in the Hollywood satire

The Big Picture.

Stunt teams deserve as much credit and compensation as possible for the spectacular destruction they orchestrate. But a sensitive eye must detect some distinction between

Smokey and the Bandit and

The Road Warrior, between

The Dukes of Hazzard and

The Matrix Reloaded—and it’s not the casting of Burt Reynolds. The latter film in each example has action scenes that aren’t simply a record of the stunt coordinator’s finesse. The flow of images in these sequences is as swooningly lyrical and transcendent as any great experimental film or musical. In

The Island, when Lincoln unleashes a truckload of giant metal wheels that slip off the flatbed and whipsaw through a convoy of mercenary SUV’s, the vehicles twist and somersault the way the assassins in John Woo’s

The Killer pirouetted to their bullet-riddled deaths. All the terms critics unpack to describe the greatest of all films apply here: Terrifying, sublime, ecstatic, convulsive, rapturous.

If Bay hadn’t created moments of pure cinema like this one in other films, one could defer much of the credit for its power to the editors, Paul Rubell and Christian Wagner. But every Bay film has a drunken outburst like this one, and he’s worked with a lot of editors.

Maybe it's in the blood: One stranger-than-fiction controversy in Bay's real life is the serious possibility that he is the illegitimate son of--no kidding--John Frankenheimer. Since a paternity test from the '80s read negative, Frankenheimer never got around to a more conclusive DNA test. But now that the legendary director is dead, the best available indicator of paternity is up on movie screens. Frankenheimer's propulsive actioner The Train quickens the pulse like a Michael Bay film, except with intelligence, restraint and something of a world view where Bay has only exasperating hyperactivity.

Mystery solved.

What's so heartbreaking about so many recent genre films is that, under the pretense of nihilism, decadence and insanity, they pulse with humanity. They remind me of Brazil's wildly overrated shoot-em-up, City of God. That film takes pleasure in the grisly child-on-child killings which occur in an urban gang war. It was edited and mixed as a rollicking rollercoaster ride, with the freeze frames and split screens of '70s exploitation. But on the level of cinematography and performance, it is as luminously humanistic as a great Renoir or Ozu. The doomed children in City of God are beautiful; their smiles and playful antics in the sun (between gunfights) invite a yearning to see more of their lives apart from the killing--a yearning that the filmmakers leave coldly unfulfilled. (The documentary Bus 174 concerns similar Rio de Janeiro slum kids but actually gathers enough evidence of its subject's human worth to leave us, yes, heartbroken when he turns full-on to violence. City of God just papers over the sadness and devastation with an audacious but trifling escalation in the carnage.)

What's so heartbreaking about so many recent genre films is that, under the pretense of nihilism, decadence and insanity, they pulse with humanity. They remind me of Brazil's wildly overrated shoot-em-up, City of God. That film takes pleasure in the grisly child-on-child killings which occur in an urban gang war. It was edited and mixed as a rollicking rollercoaster ride, with the freeze frames and split screens of '70s exploitation. But on the level of cinematography and performance, it is as luminously humanistic as a great Renoir or Ozu. The doomed children in City of God are beautiful; their smiles and playful antics in the sun (between gunfights) invite a yearning to see more of their lives apart from the killing--a yearning that the filmmakers leave coldly unfulfilled. (The documentary Bus 174 concerns similar Rio de Janeiro slum kids but actually gathers enough evidence of its subject's human worth to leave us, yes, heartbroken when he turns full-on to violence. City of God just papers over the sadness and devastation with an audacious but trifling escalation in the carnage.)