What's so heartbreaking about so many recent genre films is that, under the pretense of nihilism, decadence and insanity, they pulse with humanity. They remind me of Brazil's wildly overrated shoot-em-up, City of God. That film takes pleasure in the grisly child-on-child killings which occur in an urban gang war. It was edited and mixed as a rollicking rollercoaster ride, with the freeze frames and split screens of '70s exploitation. But on the level of cinematography and performance, it is as luminously humanistic as a great Renoir or Ozu. The doomed children in City of God are beautiful; their smiles and playful antics in the sun (between gunfights) invite a yearning to see more of their lives apart from the killing--a yearning that the filmmakers leave coldly unfulfilled. (The documentary Bus 174 concerns similar Rio de Janeiro slum kids but actually gathers enough evidence of its subject's human worth to leave us, yes, heartbroken when he turns full-on to violence. City of God just papers over the sadness and devastation with an audacious but trifling escalation in the carnage.)

What's so heartbreaking about so many recent genre films is that, under the pretense of nihilism, decadence and insanity, they pulse with humanity. They remind me of Brazil's wildly overrated shoot-em-up, City of God. That film takes pleasure in the grisly child-on-child killings which occur in an urban gang war. It was edited and mixed as a rollicking rollercoaster ride, with the freeze frames and split screens of '70s exploitation. But on the level of cinematography and performance, it is as luminously humanistic as a great Renoir or Ozu. The doomed children in City of God are beautiful; their smiles and playful antics in the sun (between gunfights) invite a yearning to see more of their lives apart from the killing--a yearning that the filmmakers leave coldly unfulfilled. (The documentary Bus 174 concerns similar Rio de Janeiro slum kids but actually gathers enough evidence of its subject's human worth to leave us, yes, heartbroken when he turns full-on to violence. City of God just papers over the sadness and devastation with an audacious but trifling escalation in the carnage.)This year, the bloodiest so far in America's War on Terror®, saw several films that delight in mass murder, torture and calamity. In Man on Fire, Denzel Washington used bombs, shoulder-fired rockets, arson and hostage-taking to terrorize an assortment of suspected child murderers. After leaving an uncounted trail of dead bystanders in streets and nightclubs, Denzel learns that the little girl he's avenging is actually alive. Oops. But director Tony Scott gives him a heroic slow-motion send-off at the end, since his questionable actions result in the freeing of Dakota Fanning. Mr. and Mrs. Smith, when not approximating the nutty grandeur of John Woo action choreography or recording the sweltering chemistry between Pitt and Jolie, celebrates the ruthlessness of American intelligence agencies.

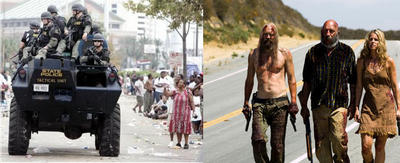

The nighttime seige pictures Hostage and Assault on Precinct 13 (both directed, interestingly enough, by Frenchmen) pay almost erotic attention to the spectacle of glass shattering under sustained automatic weapons fire and cascading to the floor like a slinky negligee. Aside from Bruce Willis and a cute little boy in Hostage, the human beings in these films are little more than a collection of grimaces, reptilian stares and hyena cackles. Retching, bleeding, cursing, screaming. Assault actually achieves the feat of being more nihilistic than the John Carpenter original without getting even half as exhilirating. Somewhere under all the shards of glass and splintered wood are resonant themes: In Hostage, the spiritual crisis of a sworn protector whose normally fail-safe instincts got innocent people killed; in Assault, the smothering sensation of being targeted by lawless lawmen, with all of society's protections working against you.

Rob Zombie's The Devil's Rejects is pure heartbreak. Zombie grew up in a family of eccentric carnival workers, known as carnies, and his first two films, House of 1,000 Corpses and Rejects, feature a clan of carny-like oddballs clearly inspired by childhood memories. But I doubt that Zombie's real-life mom and pop have slaughtered as many innocent travelers as his film characters have. In The Devil's Rejects, the serial killers have such salty Southern charm and personality, their crimes are almost forgivable. Almost. It's clear that Zombie wants the audience to take the carnage even less seriously than the funny cultural debate stitched along the film's seams. Rejects is really about the backwoods culture of country blues and corn liquor colliding with a mainstream that has no practical use for it. It's the kind of tantrum against youth-obsessed, ready-for-primetime politesse that Peckinpah almost made a subgenre.

In the wake of the New Orleans disaster, such tantrums erupted around the country, on behalf of America's rejects. Many of those swept out to sea or entombed in their basements didn't own credit cards or cars--two reasons many of them couldn't flee the city. "This is America," Oprah recently said into one of her TV cameras, tears streaming from her eyes. "These are Americans." Behind her were thousands of evacuees lying on filthy, blood-soaked mats. But there was less outrage in her eyes than uncertainty. You could sense her adding, in her mind, the question: "Are they?"

TV's condescension and casual Third World presentation of this tragedy as a matter of private charity rather than of governmental responsibility tells us that poor people are not Americans, not really. The heartbreak of American cinema is that it hardly does anything to correct its sister medium's genocidal folly.

1 comment:

Great. I love to read posts on your blog. I haven't seen it yet but I am excited to watch it. I will try to get the this movie online to watch it.

Post a Comment