(The

following is a conversation between Big Media Vandalism

founder Steven Boone and Big Media Vandalism's proprietor Odie

Henderson. It is the latest in the Black Man Talk series. Other

installments include American Gangsters, Tyler Perry, Django Unchained, 42, Lee Daniels' The Butler, Dear White People, 12 Years a Slave, Sidney Poitier, Get Out and Black Panther)

THIS IS VERY SPOILERIFIC! DO NOT READ UNTIL YOU'VE SEEN US.

Post #1: Odie

Brother Boone,

Time for another Black Man Talk! My proposed topic: Jordan Peele's new horror film, Us. It's already drawn big-league box office numbers and a ridiculous amount of thinkpieces, most of them by White folks just dying to sound woke. More power to them, but let's throw our two cents into this mix.

Speaking of the number 2, Chadwick Boseman originally held the record of two Black Man Talks and now Jordan Peele joins him in the Two-Talk club. I'd love to see what the two of them would do together, but with Boseman's track record of playing every famous brother in history from Jackie Robinson to James Brown, I'd be afraid the Boseman-Peele collab would be about a resurrected Frederick Douglass. Can you imagine Boseman as a pissed off Douglass, with grave dirt still in his hair, ringing the doorbell at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue and saying to Donald Trump "oh, so I was doing an amazing job despite being dead for a hunnert and fourteen years, huh bitch?" I'd see that movie! Twice!

We know Sam got that role locked up, tho'.

Until we get F.D.'s Revenge, let's focus on Peele's incredibly thorough mindfuck. Like Kubrick, everything in Peele's films is open for interpretation AND seems to have a genuine purpose even it it's only tangential to the main plot. Viewer theories will soon abound and they will not soon abate. Remember that documetary, Room 237, about fan theories relating to Kubrick's version of The Shining? I saw that movie at 8am on a Saturday back when I covered the Toronto Film Festival. I was hung over and in no mood for the incessant ramblings of folks who thought Kubrick used Jack Torrence to confess that he faked the moon landing. Us could beget its own Room 237, but I propose that we not venture that microscopically into Peele's delectable minutiae; sometimes a cigar is just a cigar and a pair of scissors is solely for cutting one's throat.

Besides, everybody knows that Barry Lyndon is where Kubrick owns up to faking the Moon landing. If you listen real closely, you can hear Kubrick whispering "Whitey was never on the moon!" on the soundtrack exactly every 1,969 seconds.*

*that oughta keep the Kubrick zealots busy for a while.

But I digress. I don't scare easily, but Us really got under my skin. Lupita Nyong'o played a major part in that, but let's return to her in a bit. Let me tell you why I felt a strange pang of familiarity while watching this movie.

When I was growing up broke and lonely in Jersey City, New Jersey, I amused myself with a "what-if?" scenario about my life. Like Margaret Mitchell's thot from Gone With The Wind, I swore I'd never go hungry again if I got out the 'hood, but I wondered why I was hungry and poor in the first place. My theory was that there was another Odie, my twin, and that guy got everything I wasn't getting but deserved to have. That other Odie was the beneficiary of a confused God who was sending blessings meant for me to other Odie by accident. He looked down from Heaven and was like "oh, there's an Odie! BLAM! Blessings, bitch!" So, while I seethed as a have not, my doppelganger was getting all the money and the sex and the power earmarked for me when I was placed on this Earth. Granted, the Bible tells us God doesn't make mistakes, but look at the platypus or that big ass dent in the back of my head and tell me that shit wasn't a mistake.

To solve this grievous error, I needed to find Odie Prime. "And I need to kill him!" I thought.

Now I am sure I did not craft this theory on my own. I must have read something similar to it in my literary travels, or maybe heard a story like this. But as Us played out, I thought about those old ideas--things I had totally forgotten about once I became an adult--and it made the motivations of the Tethered and Lupita's twin roles even more intriguing to me. That pang of idea recognition made me think that Us is not just a movie about the privileges and underprivileges of class, it's also about the fear of having what you deserve and/or earned violently yanked away from you by the person behind you on that perceived ladder of success.

The American psyche is nurtured and poisoned by that John Steinbeck misquote that said poor folks see themselves as temporarily embarrassed millionaires. In our lifetimes, this idea really got exploited during the Reagan era, which is where Us places its prologue. We're old enough to remember the cultural climate during Hands Across America. My mother thought it was an incredibly stupid idea to have a chain of people stretching across the country, holding hands like some church Fellowship gone viral, while making a symbolic gesture about the poor. It ran through my hometown on May 25, 1986, exactly a month before I graduated high school, and I did not go down there to participate.

Granted, Hands Across America, along with its sister cause USA For Africa, raised some money, much of it never reaching its destination. But it was such an empty gesture nonetheless, a means of allowing folks to say "I did something" when in actuality they hadn't done shit. It was the probable origin of "performative wokeness," which makes it a perfect metaphor for Peele's Tethered. They're going to do something about their situation besides hold hands and sing a shitty song.

This went to number 65 on the Billboard Chart, folks.

What do you think about my Hands Across America side-eye? And did you notice what everyone's tether looked like, especially the ones played by Elizabeth Moss and Tim Heidecker? Can you think of any film where we followed a dark skinned Black nuclear family anywhere, let alone into a nightmare? And let's also talk about the skin complexion of evil when that evil is Black. And remind me to bring up my own scary trip to Santa Cruz. Perhaps you're talking to my tethered other right now...

...nah, I'm still too many blessings short of a church picnic. It's the real me you're dealing with today.

Ride that escalator down into the depths with me, Brother Boone. The floor is yours.

Post #2: Boone

A lot of recent movies have been labeled conversation-starters but in my experience have only started fights or echo chamber circle jerks (Green Book, y'all?). Us is the first Big Ol' American Movie in a good while that seems alive with spontaneous thought and reflection rather than hashtag cues. Right now there's a cold war happening between the idea of audience as political constituency vs audience as AUDIENCE--distinct human beings going into the dark, hoping to be moved, shaken and even awed by the screen action. Get Out did a more elegant job of the latter than Us, but Us leaves, um, us with a lot more leftovers to take home.

A lot of recent movies have been labeled conversation-starters but in my experience have only started fights or echo chamber circle jerks (Green Book, y'all?). Us is the first Big Ol' American Movie in a good while that seems alive with spontaneous thought and reflection rather than hashtag cues. Right now there's a cold war happening between the idea of audience as political constituency vs audience as AUDIENCE--distinct human beings going into the dark, hoping to be moved, shaken and even awed by the screen action. Get Out did a more elegant job of the latter than Us, but Us leaves, um, us with a lot more leftovers to take home.

I'm not sure if it's Boone Prime typing these words or my wayward other, but many have suspected that the election of Donald Trump, after an unprecedented year of catastrophes and famous deaths, signaled a detour down a dark alt timeline. Soon Cosby was in prison, Roseanne disgraced, Michael Jackson tried and convicted in the court of HBO. These add up to the pop omen equivalent of birds dropping out of the sky. Us is clever enough to seize the idea of a world askew by tracing back a few decades to the moment the Evil Plan was Hatched. In that sense his project reminds me of my friend, the experimental gonzo filmmaker Damon Packard, whose surreal comedies Reflections of Evil, Space Disco, Foxfur and Fatal Pulse all look back to the 70's, 80's and 90's, searching for the poisoned roots of the present late capitalist nightmare.

Like you, me and Packard (and style-jack auteurs like Panos Cosmatos, Peter Strickland and Ana Lily Amirpour), Peele is Generation X down to the socks. While Millennials are largely interested in burning, skimming, sealing off or upgrading anything from the pop past that seems stale or irrelevant to the Now, Gen X nostalgists remember a time when the past and present existed in a chain of continuity: Then and Now are but different bends of the same river. It's a different approach from, say, Spike Lee (the world's oldest Millennial filmmaker) catering to the youthful BLM notion of "Wow, back in the 70's folks had the same struggles we do now!" which posits that the only thing that has changed are the haircuts.

A film like Us reflects that everything is always changing, that the dopplegangers are not separated by time (a la the social media memes along the lines of "Look, a pic of a 1908 Jonah Hill lookalike!") but by timeline; that in both the benevolent timeline and the evil one, there are people living out whatever life they've been given, growing older, accruing more experience, wisdom, bitterness, rot, whatever. What doesn't change is a social power structure that foresaw how to maintain its grip on the population, decades in advance. That's the real horror.

We all laughed at do-gooder stunts like Hands Across America, Live Aid, USA for Africa (We Are the World) and Do they Know It's Christmas? but it was a troubled laugh. Underneath it there was a genuine yearning for a world that wasn't so greedy and selfish. We were little kids then, born when everybody from John Lennon to Coca-Cola were trying to get everybody on earth to sing together, so we couldn't be 100% cynical about it. Peele's joke is that we're still attempting the gesture 40 years later, even as social media guarantee we needn't touch another hand, cater to or be considerate of anyone outside our networks. As has probably been noted in a dozen think pieces by now, maybe we, not the Tethered, are the Romero zombies going through the motions at the abandoned mall.

You asked for my thoughts on the "Tethered" look. The Tethered generally looked smoked, pan-seared, kind of like the vampires in Peele's '80s touchstone, The Lost Boys. The lighter skinned and white ones could be meth heads. The black Tethered looked cracked out. As Peele (ill-advisedly, IMO) gave us longer and longer looks at them, I wondered if Us could also be read as an elaborate metaphor for rehab. (Notice how the Tylers couldn't make it five minutes without a drink.) Their wine-colored jumpsuits notwithstanding, I could picture the Tethered Wilsons caught on Walmart surveillance camera boosting Cheetos.

You asked, "Can you think of any film where we followed a dark skinned Black nuclear family (two kids, but alas, no dog) anywhere, let alone into a nightmare?" Sounder? I know I'm cheating there, genre-wise, but you get what I mean. The scariest nightmare for a dark-skinned Black nuclear family is the one that slavery, Jim Crow, law enforcement and Welfare created by lawfully tearing it apart. There were many specific narrative reasons for the unstated tension in the cheerful opening car ride, but even without story context, the dissonance works for anyone who has had to live a Black Life in America.

Which reminds me, WHAT HAPPENED TO YOU IN SANTA CRUZ? Nigro, SHOW ME YOUR NECK!

Peele tips his hat to The Lost Boys by filming in Santa Cruz. I had no idea that's where they filmed my sister's favorite Coreys fllm until I went there on a work team building exercise. Considering I hate the beach, I wasn't too happy to be there, nor was I dressed for the location because my stupid, Jersey-born ass had no idea Santa Cruz had a beach. See below.

"Clueless Negro from Joisey: A Hip-Hopera"

Here's a tip for anyone who wishes to torture me: Just pour sand on my feet. I'll tell you my social security number and the few secrets I have left. Sand is my Kryptonite.

Anyway, I wound up in this creepy, dark arcade that had the video games you and I would have played growing up. I had just gotten finished whipping some teenage kid's ass on Ms. Pac-Man ("these old ass games suck!" he whimpered) when I started feeling dizzy. I went back outside, dragging my bare feet through that sand while carrying my sneakers. I became disoriented and I got lost. I remember sitting down near a ride and then the next thing I knew, I'm back at the arcade. I don't know how I got there and I didn't have my cap anymore.

So maybe this is the tethered me talking to you! (Cue creepy I Got 5 on It remix) [Ed. Note: The tethered Odie is named Garfield, for obvious reasons.]

Thank you for pointing out the meth-iness of Moss and Heidecker's tethers. I didn't consider the great rehab angle you mentioned. Instead, I thought of them as the "low class" versions of these characters, perhaps a reminder of the trailer-park world they escaped when they got some money. Despite the financial chasm that separates them, Moss and Heidecker don't seem that far removed from their tethers--the addiction's still there but the drug is more highbrow, respectable and expensive. When Moss' doppelganger garishly paints her lips in the mirror post-murder, it's as if she's saying "see, we're really no different. I'll show you." Her sudden, mutilation-fueled rejection of that notion is the creepiest shot in the film.

By comparison, Peele makes the Wilsons stew far longer in the crock pot he's thrown them into with their tethers. They seem a little more far removed, at least until Adelaide's truth is revealed. Those doubles did look like crackheads, but I also saw them as a warning to folks who made it out of the 'hood and didn't look back or help pull anyone up. The Curse of the Respectability Negro. You know them, the ones that tell you to pull your pants up, speak properly at all times and stop listening to rap. Then maybe the cops'll stop shooting ya and the White establishment will hire you at a decent salary. These are the folks who put on airs once they leave the 'hood and damn sure don't want any reminders of anything that's perceived as TOO Black; they've graduated to the pristine fashion purity of P. Diddy's white parties but don't want you to know they've still got dark-colored clothes in their closet.

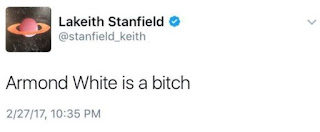

Presented without comment

I don't see the Wilsons as these types of people; Peele doesn't give us any indication and he even allows Duke's Gabe to code switch when threatened by the first appearance of the Wilson tethers. (His "I done tol' you..." bat-wielding monologue rang so familiar and so true that my mostly Black audience exploded with laughter.) But I felt the class distinction metaphor much more sharply with the Wilsons. The tethers are decked out in red, but their attire looks a lot like prison uniforms. Gabe's tether is a grunting, bearded brute who's ultimately undone by a capitalistic status symbol. Evan Alex's tether is an African myth's trickster named Pluto who shares his name with Michael Berryman's character in Wes Craven's The Hills Have Eyes, another horror film about class. (And Alex's character, Jason wears a Jaws shirt whose image evokes the torn Jaws poster on the wall in Craven's film. Told you Jordan Peele's a thorough motherfucker!)

Lupita's complex dual role is the linchpin in my theory. As we learn, Adelaide is actually a tether. This doesn't come out of the blue as far too many inattentive folks have written. Her rhythm is off in the I Got 5 on It scene. Her younger self's PTSD is actually her learning how to speak English and her ballet lessons are a means of assuming the former Adelaide's identity. When "real Adelaide" turns up as the spooky Red, she's a have who has brutally been made a have-not and is now out for revenge. I don't think there's a successful woman, brown person or LGBT person who doesn't feel a fear that what they've accomplished might be snatched away at a moment's notice by an unfair, rigged system. Because that system has only allocated X number of places not just for people like us, but also for poor folks attempting to rise from the depths of poverty. Americans have always mocked the French, but they did something we'll never have the balls to do: They banded together and killed their rich asshole oppressors.

Class as a theory is all fine and good, but what about Jeremiah 11:11 and all the Blblical/religious nuggets Peele throws at us? This intriguing article by film critic Candice Frederick sees Us as a Judgment Day allegory, which isn't far-fetched when you realize Jeremiah 11:11 evokes the angry Old Testament God I understood far better than Jesus when I was a kid:

"Therefore thus saith the Lord, Behold, I will bring evil upon them, which they shall not be able to escape; and though they shall cry unto me, I will not hearken unto them."

"Therefore thus saith the Lord, Behold, I will bring evil upon them, which they shall not be able to escape; and though they shall cry unto me, I will not hearken unto them."

In that quote, de Lawd is basically saying "Fuck Yo' Couch, Nigga!"

Michael Abels' score does use that creepy Omen-style chanting which implies religion-based terror, but I think all the Biblical stuff is a red herring. What do you think about Frederick's theory? Any other symbolism you wish to riff on? I'd like to riff on the skin color of Black villains in horror movies next time. And let's talk about the brilliance that is Lupita Nyong'o and the unfair advantage that is Winston Duke's thighs. And the rabbits! This is the second time Peele has taken a seemingly innocent animal and recast them as a symbol of violence. What's up with that?

Post #4: Boone

Ms. Frederick's piece on Us as a group portrait of faithless self-absorption resonates (though she coyly avoided the Adelaide/Red spoiler).

At one of Clay McLeod Champan's brilliant public horror talks a few years back, the consensus fear among panelists turned out to be the fear of losing control of one's mind and body. I couldn't quite relate. My overwhelming fear, having grown up around shootouts and drug raids, was not of losing control of mind/body but of losing mind/body. Dying. To be alive in any form beats entering the void and its unknowns. As Redd Foxx (whose analysis of Us I would love to hear) put it, "There's a lot of things worse than cancer. A six foot six black nationalist in an alley with a hatchet, mad at ya... is worse than cancer."

Similarly, I didn't have much of a visceral response to the primary fear Us is stoking: the fear that the relative privilege and comfort "we" enjoy will eventually come with a bloody bill. American horror has always been about shattering apparent safe spaces and making happy people pay for their pleasures. But the (thinkpiece-speak ahoy!) post-Zuckerberg social world we live in now delivers fitful, anxious, lonely pleasures--ephemeral crack-hits of hope, confidence and community that never escape bloody reality. Old school escapism is dead. Or maybe I should just speak for my algorithms, which deliver beauty and excitement at one scroll, GoPro snuff films and utter ratchet-ness at the next. There is no calm that the arrival of Boone-Tether could shatter.

Big Media Vandalism Artist's rendition of Boone's Tether

The Tethered actually deliver the Wilsons an inadvertent gift, sort of the way the home invaders in Straw Dogs awakened meek Dustin Hoffman to his essential manhood. The Wilsons briefly become a coordinated, unified force while battling the Tethers at the Tylers'--even if their victory quickly lapses into a (pretty clever, funny) debate over who notched the most kills--as if huddled around a Playstation. Suddenly, they're alive with purpose in a film crowded with mindless stragglers.

It's the vitality of the fight that I appreciated as something "real" in contrast to the convoluted symbolism of the Tethered, which is more of a clever puzzle than an immediate source of terror. Even so, Lupita Nyong'o sells the hell out of it. Her panic as Adelaide and malevolent wretchedness as Red (or vise versa) give the action a weight it might otherwise have been missing. Also, she is impossible to look away from. Lawd. Has there ever been a woman this simultaneously dark and lovely holding the center of the big screen? She is a gorgeous rebuke to a 125-year old lie.

As for the ballet motif, I may have misread it as Adelaide's memory of her last moments of freedom and dreaming of a future before she got trapped in Tethered hell. But I'll just have to go watch Us again to be sure.

The rabbits didn't do much for me. Maybe Peele nurses a phobia or some serious Watership Down PTSD, but, as signifying animals go, those rabbits can't top Black Philip, the scary-ass billygoat in The Witch.

I feel you on the notion of how important skin color is in this film, as it was in Get Out. Tell me about it.

The Final Word: Odie

That Vox video about skin color you cited above was an eye-opener. It shows how little we mattered to Hollywood and to the historical record in general. The fact that film colors were measured and calibrated with White skin didn't surprise me at all; the fact that this practice continued well into the '80's and '90's did surprise me. It makes you wonder how much harder it must have been for Gordon Parks to take those magnificent pictures for Life.

Us's use of dark-skinned protagonists seems novel, but the skin color of their villanous doppelgangers is far more prevalent in Hollywood movies, especially horror. Years ago on this very site, I wrote a piece about Black horror movies. Most of the villains in those films tended to skew darker-skinned. Hollywood Shuffle takes a swipe at this notion in its Black Acting School skit. Peele's casting plays like one corrective amongst many; in Us he has several scores to settle. As Monica Castillo points out in her four-star review over at Roger's, the house of mirrors Adelaide enters is branded with Native American imagery in the flashback, yet when she revisits it, the site has been rebranded as if to hide its sordid racial past. Peele's tying of the Tethered to the first Americans who were robbed by colonizing White men offers a form of payback for this country's original sins.

That Vox video about skin color you cited above was an eye-opener. It shows how little we mattered to Hollywood and to the historical record in general. The fact that film colors were measured and calibrated with White skin didn't surprise me at all; the fact that this practice continued well into the '80's and '90's did surprise me. It makes you wonder how much harder it must have been for Gordon Parks to take those magnificent pictures for Life.

Us's use of dark-skinned protagonists seems novel, but the skin color of their villanous doppelgangers is far more prevalent in Hollywood movies, especially horror. Years ago on this very site, I wrote a piece about Black horror movies. Most of the villains in those films tended to skew darker-skinned. Hollywood Shuffle takes a swipe at this notion in its Black Acting School skit. Peele's casting plays like one corrective amongst many; in Us he has several scores to settle. As Monica Castillo points out in her four-star review over at Roger's, the house of mirrors Adelaide enters is branded with Native American imagery in the flashback, yet when she revisits it, the site has been rebranded as if to hide its sordid racial past. Peele's tying of the Tethered to the first Americans who were robbed by colonizing White men offers a form of payback for this country's original sins.

Since we started doing this talk, a lot of different reviews have come and gone. Several of my non-critic friends expressed disappointment that the film wasn't cut and dry, that it didn't explain everything. A few of those guys also complained about "plot holes" and being left to their own devices to figure things out. Granted, this is not as neat as Get Out, which zeroed in on the specificity of being Black in dangerous White spaces, but I found the film's messiness to not only be rewarding but it also pays new dividends every time one thinks about it. Walking out, I thought of our good buddy Matt Zoller Seitz, who lives for shit like this.

Since I've got the last word here, I want to big-up all the performers in Us. Lupita deserves all the praise and then some for creating a dual role that's ripe with complexities that reveal themselves over several viewings. She rocks her final scene with Pluto, which is the moment where Peele almost tips his hand for those of us who wondered if she were actually a tether (his decision to have Jason walk backwards before Adelaide's empathy becomes too noticable is a clever one). But she's in good company with Evan Alex and Shahadi Wright Joseph, who also bring a similar richness to their dual roles. And lest we forget M'ThighU, i mean Winston Duke, who has just the right touch of goofy playfulness as Gabe, and just the right touch of menace as Abraham.

To close out, you said:

"The Tethered actually deliver the Wilsons an inadvertent gift, sort of the way the home invaders in Straw Dogs awakened meek Dustin Hoffman to his essential manhood. The Wilsons briefly become a coordinated, unified force while battling the Tethers at the Tylers'--even if their victory quickly lapses into a (pretty clever, funny) debate over who notched the most kills, as if huddled around a Playstation."

I want to take that unity a step further. At first, when the Tylers' tethers turned to attack the Wilsons, I thought it was due to their visual branding as redneck-y White folks. Of course they'd go after the Black folks! They're racist! But, in hindsight, I realized instead that their actions showed how united a front the Tethers had. The have-nots have finally come together, no longer put asunder by the endless blame babble regurgitated by Fox News, the GOP and the right-wing nutjobs whom mainstream media outlets like CNN and MSNBC can't help but amplify in their lustful quest for ratings. It no longer made a difference what color the Tethers were; they had finally realized that a common enemy had boots on everyone's neck. If poor White folks finally realized that the powers-that-be actually saw them as no better than the folks they're supposed to hate and blame, there would be the kind of reckoning only hinted at by the bird's-eye view of the endless stream of Tethers in the final shot of Us.

Now, that's a sequel I'd like to see.

"I hate to cut this Black Man Talk short, but..."